Even though we can’t celebrate Halloween as we used to in the era of COVID-19, jellyfish costumes are among the most popular and beautiful. In honour of October 31, let’s talk a little more about invertebrates in the Class Medusozoa, also known as jellyfish!These animals have been living in the world’s oceans for more than 700 million years. They are very simple morphologically: their bodies are mostly water (98%) with a gelatinous tissue layer, a rudimentary nervous system and thousands of stinging cells in their tentacles used to capture pray. Despite their simple appearance, some species have up to 24 eyes that they use to “see” their environment.

Toxicity among jellyfish varies widely. Most of the toxins they hold within their stinging cells can produce pain in humans, and some can kill a human in minutes. Among the most poisonous are the tiny box jellyfish – mostly found around Australian waters – which can carry venom capable of killing 60 humans.Jellyfish size ranges from tiny animals with bell disks no more than 0.5 mm in diameter, to huge animals with bell disks of 2 m (Nomura’s jellyfish, Nemopilema nomurai). Some even exhibit tentacles measuring up to 37 m (Lion’s mane jellyfish, Cyanea capillata)!

JELLYFISH NUMBERS APPEAR TO BE INCREASING

Did you know that a group of jellyfish are called a “smack”? In some regions, jellyfish are proliferating even during seasons they usually weren’t around. There could be a number of reasons for these non-expected peaks, however overfishing and pollution seems to be the main causes. Few animals feed on jellyfish due to their low nutrient content and high number of stinging cells filled with toxins, some of these animals are sea turtles, red tuna and swordfish, all of them are currently endangered species due to overfishing. Coastal water nutrient enrichment, also known as pollution, is resulting in an increase of plankton which is the main food for jellyfish. In addition, some studies have shown that warmer temperatures and ocean acidification are beneficial for jellyfish reproduction, increasing the number of offspring. Therefore, with global change jellyfish peaks can be the new normal even in sites never been seen before. As a response, in some countries people are starting to explore ways to eat them; would you try them?

JELLYFISH IN THE BAHAMAS

In The Bahamas, jellyfish can be found in different marine ecosystems and there are few species that are seasonal. In muddy areas like seagrasses and mangroves, the upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea xamachana) is very common, as is the moon jelly (Aurelia aurita) in coastal areas swimming in the first 20 m depth. Both have stinging cells that can cause pain or adverse reaction in humans. The upside-down jellyfish can even deliver mucus containing free stinging cells that sting in the water!

Photos: Valeria Pizarro & Natalia Hurtado

Become a PADI Dive Instructor in The Bahamas | Conservation-Focused IDC

Become a PADI Dive Instructor in The Bahamas | Conservation-Focused IDC | Perry Institute for Marine Science Education & Training Ready to take your diving skills to the next level

Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen

Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen | Perry Institute for Marine Science Conservation Partners Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen Discover why PIMS has partnered with

Build a Coral Reef for the Holidays | PIMS x Partanna

PIMS is partnering with Partanna to build a 100m² carbon-negative reef. Rick Fox is matching donations up to $25k. Help us build a sanctuary for the future.

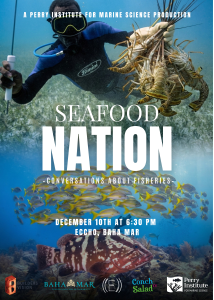

“Seafood Nation” Documentary Premiere Explores the Heart of Bahamian Culture and the Future of Fisheries

NASSAU, The Bahamas | December 5, 2025 – From the bustling stalls of Potter’s Cay to family kitchen tables across the archipelago, seafood is far more than just sustenance in

PIMS and Disney Conservation Fund Partner to Train 19 Government Divers

PIMS dive training in Nassau strengthened national coral restoration capacity across government agencies. Bahamas Dive Training Builds National Coral Restoration Capacity Last fall, between the months of September and October,

Florida’s Coral Reef Crossed a Line: What Functional Extinction Really Means for Elkhorn and Staghorn Corals

Reefs didn’t just bleach. They functionally vanished in one summer. A new Science study co-authored by researchers from the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) has found that Florida’s two