An Overview – Written by Lily Haines

“We saw all sorts of things you typically don’t see on reefs… vacuum cleaners, pieces of construction and roofing materials, plumbing materials, laptops and lawnmowers,” said Dr. Krista Sherman, Senior Scientist at the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS).Last week, Drs. Craig Dahlgren (Executive Director, PIMS) and Krista Sherman revealed that approximately 30% of reefs surveyed off Abaco and Grand Bahama had suffered physical damage from Hurricane Dorian. This was one of the key take-aways from the “Hurricane Dorian: Impacts Below the Surface” virtual panel event, presented by Changing Seas Live and hosted by both the Angari Foundation and WPBT2 South Florida PBS.PIMS surveyed close to 70 coral reef sites off the Little Bahama Bank a month before Hurricane Dorian made landfall in The Bahamas, and again several weeks later. Using the Atlantic Gulf and Rapid Reef Assessment protocol, divers evaluated the amount of live coral cover at each site, as well as coral condition (i.e., the percent of diseased coral, bleached coral, etc.), benthic and fish population dynamics.

Photo by Kevin Davidson, Angari Foundation

Coral Reef Health in the Wake of Hurricane Dorian

Interestingly, coral reef damage within the path of Category 5 storm was highly variable. Losses to coral cover off Abaco’s nearshore Mermaid Reef, which bolsters some of the highest live coral cover in The Bahamas, were extensive. “Some colonies were picked up and moved 20-30 metres away from the reef…,” said Craig. Other nearshore sites were left mostly unscathed, while reefs miles away from the eye of the hurricane were significantly impaired.Craig and Krista also observed extensive coral bleaching in the wake of Hurricane Dorian, particularly on deeper sections of the reef. Coral bleaching occurs when corals expel their zooxanthellae; that is, the colourful, photosynthesizing symbiotic algae that live within their tissues. This phenomenon, which typically results from severe ocean temperature shifts, gives corals a “bleached” or white appearance; bleaching stress can often lead to coral mortality.The catch here, of course, is that ocean temperatures didn’t increase during Hurricane Dorian. So why did the corals bleach? The running hypothesis is that Hurricane Dorian deposited extensive, muddy sediment onto the corals, which may have led to bleaching. “We looked at satellite images from right after the storm,” said Craig. “The water was like chocolate milk… far from our typical crystal-clear Bahamas blue.” If light was unable to sufficiently penetrate through the turbid water column to reach deep-dwelling corals, then zooxanthellae may have stopped photosynthesizing for several weeks. Many corals may have bleached (i.e., expelled their algae symbionts) as a result.For PIMS, the next steps are to: 1) continue monitoring coral reefs for possible long-term impacts from Hurricane Dorian and 2) evaluate the environmental conditions that different reefs experienced during the storm to better understand why coral reef damage was so variable.

Photo by Kevin Davidson, Angari Foundation

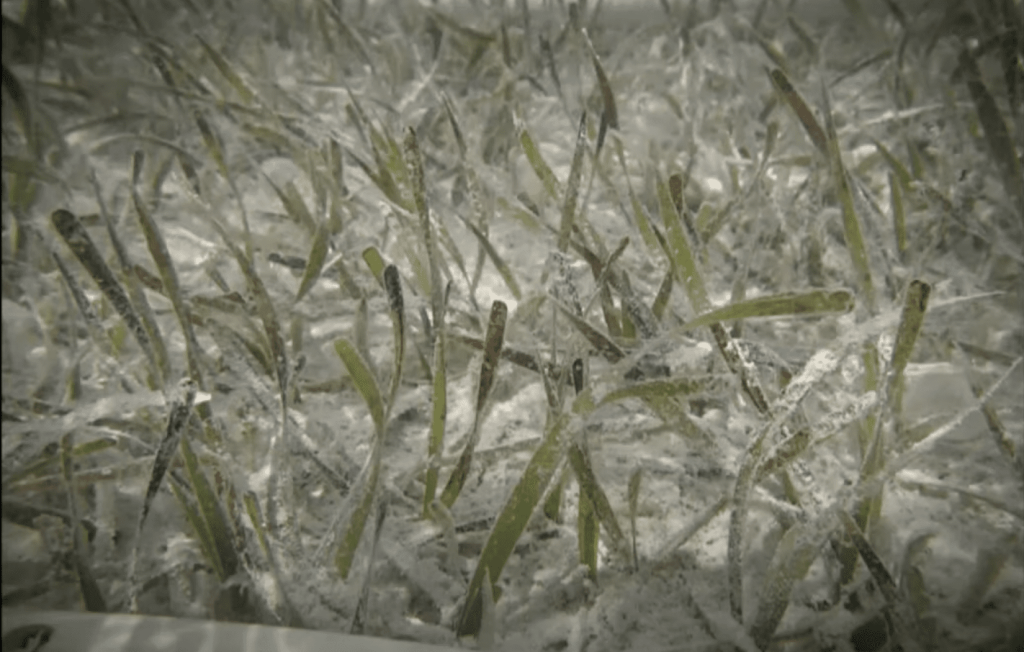

Documenting Changes to Seagrass Habitats

In the panel discussion, Craig and Krista were also joined by experts from The Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organization (BMMRO; Executive Director Dr. Diane Claridge and President Dr. Charlotte Dunn), as well as Executive Director Dr. Cha Boyce from Friends of the Environment.The BMMRO has kept busy documenting changes to the diversity and productivity of seagrass beds since the storm. Seagrass beds, like coral reefs, are among the earth’s most productive ecosystems, and harbour diverse communities of fish, invertebrates, marine mammals and birds. “Studies have found that mass destruction of seagrass beds can affect the health of top predators, like coastal dolphins,” said Diane.Diane and Charlotte documented the diversity of seagrass and macroalgae at seven different shallow-water mangrove sites, beginning in South Abaco and moving north, following the direct path of the storm. They conducted surveys three months after the storm, and again six months later.“As we feared, we discovered some dramatic changes…” said Diane. “Before Hurricane Dorian, turtle grass was the dominant seagrass species. After the hurricane passed, turtle grass was replaced with other seagrass species, namely shoal grass and manatee grass, which are often prevalent in areas where there’s been dredging or disturbance to the habitat.”Unlike shoal and manatee grass, turtle grass beds create extensive root networks that easily retain sediments. The transition away from turtle grass-dominated systems could therefore reduce sediment retention in mangrove systems, and ultimately lead to more turbulence and mud deposited onto reefs during future storm events. What’s more, this transition could lead to a potential decrease in invertebrate abundance because turtle grass beds, and their overall larger biomass, offer more shelter for invertebrates.

Photo by the BMMRO

Rebuilding After the Hurricane

As a resident of South Abaco, Dr. Cha Boyce, the Executive Director of Friends of the Environment, described what it was like to live through the worst hurricane in Bahamian history.“Nobody could have ever imagined the devastation… during the eye of the storm, it was calm and we were able to go outside, and we realized how bad it really was,” she said. “Our neighbours houses had been completely flattened… water levels were rising… there’s no way we could have been prepared.”Hurricane Dorian’s ferocious 185-mile winds, 220-mile gusts and tsunami-like waves ravaged The Bahamas for nearly three days. Storm surges reached 20 feet. Hundreds of lives are estimated to have been lost.“Many people are still struggling and don’t have access to shelter, running water and electricity,” said Cha, reflecting on the past year of recovery efforts in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic.Friends of the Environment lost its education centre, as well as its office building. The research centre, however, was minimally damaged and this facility was offered as a dry space for relief efforts coming in.In January, Friends of the Environment worked with local diver operators and the US-based non-profit, Eco Blue Projects to clean up the debris-ridden Mermaid Reef.“We were able to bring in school children to help with loading up the debris,” Cha said. “Many of these kids had never put on a mask and snorkel and looked under the surface of the water before, so it was really impactful.”To watch the panel and learn more, check out the Youtube link at the top of this page!

Photo by Will Greene, PIMS

A Year Later, Stranded Tug and Barge Still Scars Reef in Fowl Cays National Park–Residents Demand Accountability

A haunting aerial view of the grounded tug and barge in Fowl Cays National Park—still embedded in coral a year later, a stark reminder of the cost of inaction. Photo

Women Leading Mangrove Restoration in The Bahamas

Have you ever wondered who’s behind the scenes saving our environment, right in our own backyard? Picture a group of energetic, determined women rolling up their sleeves and diving into

Rewilding the Marls of Abaco: PIMS Plants 100,000 Mangroves and Counting in 2024

As the afternoon sun bathes the Marls of Abaco in golden light, Bahamian boat captain Willis Levarity–locally known as “Captain to the Stars”–stands ankle-deep in soft, warm mud. A broad

Unveiling Coral Reef Biodiversity: Insights from ARMS Monitoring Structures

An ARM teeming with new coral recruits and a diversity of marine life, highlighting reef recovery and biodiversity Understanding Coral Reef Biodiversity Most new PhDs in the natural sciences move

7 Key Takeaways from COP16: Confronting Coral Reef Challenges in a Changing Climate

United #ForCoral: Experts, advocates, and leaders from across the globe join forces at COP16 for the #ForCoral conference, hosted by the International Coral Reef Initiative. Together, they’re driving urgent action

Fieldwork Wrap-Up: Strengthening MPA Management in The Bahamas

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are critical tools in the conservation of marine species and habitats, safeguarding reefs, seagrasses, and mangroves that provide vital ecosystem services to coastal communities. At the