Marine researchers from the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) and the Bahamas National Trust (BNT) collaborate for an expedition in the southern Bahamas.

The Vital Role of Coral Reefs and Seagrass Beds

Coral reefs and seagrass beds are highly productive marine habitats supporting biodiversity and providing vital ecosystem services to coastal nations like The Bahamas. However, these habitats face increasing changes due to natural and human-related stressors such as climate-induced coral bleaching, hurricanes, overfishing, and diseases like stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD).

Conducting the Marine Rapid Ecological Assessment

During July 7-19, 2024, Dr. Krista Sherman, Senior Scientist and manager of the Fisheries Research & Conservation Program with the Perry Institute, led a rapid ecological assessment of Little Inagua marine life. The expedition aimed to evaluate the condition of coral reefs and seagrass beds essential for commercially and ecologically valuable fish (e.g., groupers, snappers, parrotfish) and invertebrates (e.g., spiny lobster, queen conch, long-spined sea urchins, sea cucumbers).

The survey team included PIMS staff (Dr. Sherman, Dr. Valeria Pizarro, Natalia Hurtado, Maya Gomez, Candice Brittain) and Lindy Knowles (Bahamas National Trust). Over seven days, the team scouted 25 sites, surveying 13 reefs and four seagrasses around the island. They revisited five reefs initially surveyed in 2011 during the Global Coral Reef Expedition launch. All surveyed sites are within Little Inagua National Park, the second-largest protected area in the southern Bahamas.

Established in 2002, the Little Inagua National Park is an uninhabited no-take marine and terrestrial protected area covering ~254 km2 (62,800 acres) and it is managed by BNT. Senior Science Officer and Acting Director of Science & Policy for BNT, Lindy Knowles completed benthic surveys and drone flights during the expedition. “This park is one of 32 national parks managed by BNT, but it has been, for many years, a mystery. It’s remote, a bit secluded and yet so beautiful”. Reflecting on the trip he stated, “We now have a better idea of how the habitats in the park are doing. Corals have been bombarded by SCTLD but the seagrass beds are intact, which shows that the entire system is relatively stable. It was surprising not to see any coastal mangrove creeks, but we did see in-land wetlands and buttonwood trees”.

Observations and Findings

PIMS Senior Scientist and manager of the Coral Program, Dr. Pizarro expressed her delight in observing healthy colonies of some corals including brain corals, flower corals and star corals that are susceptible to SCTLD. She noted, “I was so happy to see juveniles of the smooth flower coral (Eusmilia fastigiata) after SCTLD has killed most of these colonies in other parts of The Bahamas”. Unfortunately, all the pillar corals (Dendrogyra cylindrus) observed on the trip were killed by SCTLD.

In addition to struggling with the impacts of SCTLD, reefs throughout much of The Bahamas took a beating during last summer’s heatwave. In Little Inagua, we saw evidence of this devastating disease and bleaching on various species. Some coral colonies perished while others survived. We visited one patch reef where large 4-5 m colonies of mountainous and boulder star corals (Orbicella spp). were thriving with no evidence of SCTLD, other coral diseases or bleaching. However, large stands of elkhorn (Acropora palmata) and staghorn coral (A. cervicornis) at this site weren’t so lucky and likely died from bleaching.

The Diverse Marine Life Around Little Inagua

There is still much life around Little Inagua’s reefs ― with large vase and barrel sponges, turtles, stingrays and sharks. The fish and invertebrate communities appear to be in relatively good condition, which is great news for sustaining fisheries outside the park’s boundaries. Large and medium-sized predators like barracudas, groupers and snappers were present at most sites along with different types of herbivores including parrotfish and surgeonfish. “I don’t remember ever seeing so many coneys and barracudas” noted, Dr. Sherman. “It was also really cool to consistently see black durgon and sargassum triggerfish at some sites since they’re not typical in other parts of the country”, she said. Key economically valued invertebrates, including the Caribbean spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) and queen conch (Aliger gigas) also seem to be doing well.

The Future of Conservation Efforts

It is unlikely that another expedition will be conducted around Little Inagua National Park within the next 8-10 years. Dr. Sherman shared “The data we collected over the course of this expedition will be analyzed in the coming months. This information will be important to help protect biodiversity and preserve the integrity and function of Little Inagua’s marine ecosystems”.

PIMS is extremely grateful for the continued partnership with the International SeaKeepers Society, which connects researchers with vessels through its Discovery Yacht Program. The team’s home and field office for 12 nights and 13 days was a 63 ft sailing catamaran called the Awatea Adventures. Haley Davis, Citizen Science Manager for SeaKeepers said, “We are excited about the opportunity to engage private vessels for important scientific work and we are more than happy to have used the Awatea as a low-carbon option for this two week liveaboard voyage. The Little Inagua expedition was made possible by a grant from the Moore Bahamas Foundation to PIMS, BNT and SeaKeepers.

For more information about our applied conservation research on fisheries, coral reefs and coastal ecosystems, visit our website and follow PIMS on Facebook and Instagram at @perryinstituteformarinescience.

Dive deeper.

Build a Coral Reef for the Holidays | PIMS x Partanna

PIMS is partnering with Partanna to build a 100m² carbon-negative reef. Rick Fox is matching donations up to $25k. Help us build a sanctuary for the future.

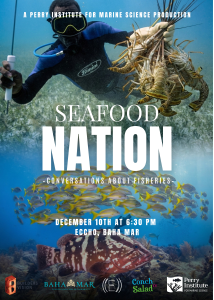

“Seafood Nation” Documentary Premiere Explores the Heart of Bahamian Culture and the Future of Fisheries

NASSAU, The Bahamas | December 5, 2025 – From the bustling stalls of Potter’s Cay to family kitchen tables across the archipelago, seafood is far more than just sustenance in

PIMS and Disney Conservation Fund Partner to Train 19 Government Divers

PIMS dive training in Nassau strengthened national coral restoration capacity across government agencies. Bahamas Dive Training Builds National Coral Restoration Capacity Last fall, between the months of September and October,

Florida’s Coral Reef Crossed a Line: What Functional Extinction Really Means for Elkhorn and Staghorn Corals

Reefs didn’t just bleach. They functionally vanished in one summer. A new Science study co-authored by researchers from the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) has found that Florida’s two

Q&A: Understanding the IDC Course at PIMS with Duran Mitchell

A former aquarist turned coral conservationist, Duran is passionate about understanding how all marine life connects. PIMS & IDC: Empowering New Dive Instructors for Marine Conservation PIMS & IDC: Empowering

Forbes Shines a Spotlight on Coral Reef Restoration in the Caribbean

When Forbes highlights coral reef restoration, it signals something powerful: the world is paying attention to the urgent fight to protect reefs. And solutions are within reach. Recently, Forbes featured Dr. Valeria