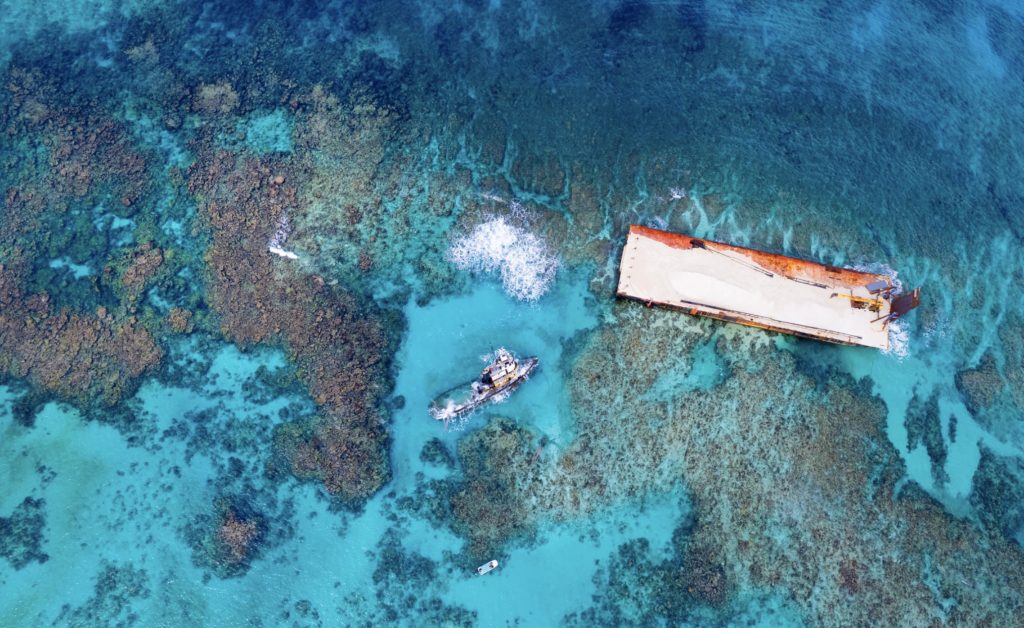

Stranded Tug and Barge in Fowl Cays National Park: One Year Later

March 27, 2025—ABACO | A full year has passed since fierce winds and churning waves threw a tugboat and barge onto the delicate corals of Fowl Cays National Park. Despite multiple attempts to free the vessels, they remain a rusting eyesore—and a threat to the reef’s future. Locals, dive operators, and a coalition of nonprofits, led by the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS), want to know: why hasn’t it moved?

Stories of ships running aground in The Bahamas are nothing new. Every year, Abaco draws a steady stream of boaters, from local fishing craft to visiting megayachts. News reports and marine experts note that dozens of groundings occur each year, with foreign-flagged vessels often contributing a significant share of incidents.

Local boats remain vulnerable to the same hazards, but tourism traffic often brings captains less familiar with the region’s shallow channels and tricky reefs.

David Knowles, Chief Park Warden at The Bahamas National Trust (BNT) overseeing all national parks in Abaco, vividly recalls the day the tug and barge slammed onto the reef. “It’s the same story we’ve seen again and again,” he says. “Weather shifts, a channel is miscalculated, and suddenly a boat is on the reef. But what’s unique here is how long it’s stayed.” BNT, which manages Fowl Cays National Park along with more than 30 other protected areas, quickly issued a public statement after the grounding, urging the vessel’s immediate removal to prevent further damage.

How the Grounded Vessel Continues to Damage Coral Reefs in The Bahamas

The barge, reportedly loaded with construction supplies bound for a development on Abaco, poses ongoing hazards to divers and boaters, with twisted beams and stray materials scattered across the seabed.

Over the past year, authorities and salvage teams have attempted to refloat the tug on four separate occasions without success. During these attempts, the tug’s stern repeatedly grounded on an adjacent section of reef, pulverizing corals below into rubble and sand.

Part of the frustration stems from a simple question: who should pay to fix this? Under Bahamian law, the owner is legally responsible for the salvage, environmental remediation, and the safe removal of any cargo. But in practice, these groundings often become a bureaucratic tangle.

Local Communities and Divers Demand Action to Protect Abaco’s Marine Life

“It’s easy to point fingers at those in charge,” says Denise Mizell, Abaco Program Manager for PIMS who has organized major cleanup efforts at the site since its grounding, “but they can only do so much without cooperation and funding from the owner’s insurance. Meanwhile, corals keep getting crushed, and people who treasure these waters feel powerless.”

Guided by its vision—“Thriving Seas, Empowered Communities”—PIMS is a global nonprofit that uses science to discover new solutions, create opportunities for people, and inspire action to protect ocean life. Their work spans coral reefs and mangroves, sustainable fisheries research, and education programs in The Bahamas. By collaborating with local communities, PIMS helps create sustainable job opportunities in ocean conservation, encouraging environmental stewardship and supporting family livelihoods.

Working side by side with Friends of the Environment (FRIENDS), Bahamas National Trust (BNT), Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation (BMMRO), local dive shops, and volunteers, PIMS has led efforts to remove debris from the barge still harming the reef. According to divers on these missions, the cargo of pea rock and sand from the barge spilled overboard, covering reef-building corals and smothering fragile habitats. Divers have collected rope, planks, twisted metal, and other debris drifting onto the reef, sometimes fire extinguishers, chart books and plastic light covers mixed among shattered elkhorn coral. Elkhorn coral, categorized as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), is one of the Caribbean’s most important reef-building species.

For many Bahamians, that image cuts to the heart of the issue. The country’s famed coral reefs, especially the branching elkhorn coral that shelters fish nurseries, have already been hammered by disease, hurricanes, and pollution. Tourists come from around the globe to snorkel and dive here, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into the local economy. Meanwhile, a single grounding can devastate decades of coral growth and disrupt the ecosystem that supports tourism and contributes to nearby fisheries. When storms roll in, the tug and barge shift, scraping the reef anew. Ropes snag, anchor chains drag, and once-vibrant coral heads splinter under the weight of shifting metal.

“It’s gut-wrenching to see such negligence,” says Troy Albury of Dive Guana. As President of Save Guana Cay Reef and Fire Chief for Guana Fire and Rescue, he wears many hats in this close-knit community. Albury regularly leads underwater tours and has watched debris from the stranded barge creep into neighboring dive sites. “It’s a threat to everything people love about Abaco—the fish, even the tourism jobs. Every week, visitors ask, ‘Why is there a barge on the reef?’ and I don’t have a good answer.”

The Legal Responsibility Behind Ship Groundings in The Bahamas

The Government has powerful tools on paper. Under the Environmental Planning and Protection Act of 2019 and international conventions like the Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks, owners must carry wreck removal insurance and face stiff penalties if they fail to remove a grounded vessel. The Port Department can also coordinate with other agencies to order salvage operations, or, in some cases, remove the vessel itself and bill the owner.

Olivia Patterson-Maura, Executive Director of Friends of the Environment —whose environmental education and conservation programs are a renowned staple in the Abaco community—believes that lasting solutions require government and private stakeholders to pull together. “Everyone wants to protect The Bahamas’ reefs—tour operators, local communities, government agencies,” she says. “We really want to collaborate on practical steps that get the wreck out of the park and restore the site, but we need more than non-profit organizations to step up to the plate. This is a national treasure, and it’s in all our interests to remove it before more damage occurs.”

How Community-Led Conservation Is Making a Difference

The tug and barge lie about half a mile from a coral nursery run by the Reef Rescue Network—a collaborative restoration effort led by PIMS and local stakeholders—where fragments of elkhorn and staghorn corals are grown with the hope of replanting them on endangered reefs. Each time storms agitate the stranded vessels, divers see more broken coral littering the seafloor.

“Every time the tug shifts in heavy swells, it scrapes away more of the reef. We’ll dive back down and find broken coral colonies, half-buried gorgonians, and fresh rubble. It’s heartbreaking to watch the corals get pounded over and over,” said Dr. Charlotte Dunn, a volunteer diver and President of The Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, non-profit dedicated to long-term field studies of marine mammals in The Bahamas.

In the face of shifting winds and unreliable actors, community members are stepping up. Residents who rely on these waters for fishing, diving, and tourism wait anxiously for updates, questioning when visible progress will finally happen. Few doubt the complexity of large-scale salvage jobs. Yet the question remains: in a place where coral reefs generate hundreds of millions of dollars in tourism revenue and shield coastlines from storms, how can a stranded barge be allowed to linger an entire year?

Mizell and her volunteer teams plan to return to the wreck site soon, armed with gloves, mesh bags, and determination to collect whatever new debris has dislodged. Each dive might remove only a fraction of the junk, but for those who love these waters, every fragment is worth saving. When asked why they persist with such incremental work, Mizell’s answer is simple: “We do it because we all care about the state of our ocean. The reef can’t wait.”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Who is responsible for removing grounded vessels in The Bahamas?

Under Bahamian law and international maritime conventions, the Government can hold vessel owners legally responsible for removal, salvage, and environmental remediation.

2. How is the grounded barge affecting coral reefs in Abaco?

The barge continues to destroy reef-building corals like elkhorn and staghorn by shifting in storms and scattering debris, leading to further damage and destruction of the reefs

3. What actions are being taken by local organizations?

Nonprofits such as PIMS, BNT, BMMRO, and FRIENDS are leading cleanups, organizing divers to remove debris and minimize harm while calling for government intervention and insurance accountability.

4. What’s the economic impact of reef damage in Fowl Cays National Park?

Coral reefs drive tourism and protect coastlines. Damage here jeopardizes tourism income, fish nurseries, and the long-term ecological and economic health of Abaco.

5. Can the reef recover once the vessels are removed?

With coordinated restoration—including coral nursery programs and debris cleanup—some recovery is possible, but the longer the wreck remains, the harder restoration becomes.

Dive Deeper

Thriving Fish Spawning Aggregation Inspires Hope for the Future

Nassau grouper FSA in Ragged Island during January 2025. | © André Musgrove Fish Spawning Aggregations & Nassau Grouper Imagine witnessing thousands of fish gathering in a synchronized spectacle, moving

A Year Later, Stranded Tug and Barge Still Scars Reef in Fowl Cays National Park–Residents Demand Accountability

A haunting aerial view of the grounded tug and barge in Fowl Cays National Park—still embedded in coral a year later, a stark reminder of the cost of inaction. Photo

Women Leading Mangrove Restoration in The Bahamas

Have you ever wondered who’s behind the scenes saving our environment, right in our own backyard? Picture a group of energetic, determined women rolling up their sleeves and diving into

Rewilding the Marls of Abaco: PIMS Plants 100,000 Mangroves and Counting in 2024

As the afternoon sun bathes the Marls of Abaco in golden light, Bahamian boat captain Willis Levarity–locally known as “Captain to the Stars”–stands ankle-deep in soft, warm mud. A broad

Unveiling Coral Reef Biodiversity: Insights from ARMS Monitoring Structures

An ARM teeming with new coral recruits and a diversity of marine life, highlighting reef recovery and biodiversity Understanding Coral Reef Biodiversity Most new PhDs in the natural sciences move

7 Key Takeaways from COP16: Confronting Coral Reef Challenges in a Changing Climate

United #ForCoral: Experts, advocates, and leaders from across the globe join forces at COP16 for the #ForCoral conference, hosted by the International Coral Reef Initiative. Together, they’re driving urgent action