By Dr. Craig Dahlgren, Executive Director, PIMS

Shark and sea turtle conservation in The Bahamas has recently re-emerged as a contentious issue. Since 2011, The Bahamas has been a shark sanctuary with a full prohibition on shark fishing, and since 2009 the harvest of sea turtles has been illegal. Both measures were implemented due to dramatic declines in shark and sea turtle populations. Several species of sharks and sea turtles are listed as endangered or critically endangered, and most others are vulnerable to extinction with their populations trending downwards.

Recently there have been calls to remove protective bans for sharks and sea turtles and potentially allow culling of their populations. This request is based on the assertion that shark and sea turtle populations have increased to the point where they have become a “nuisance and a danger to fishermen,” and compete with fishers for catching conch, lobster and fish. As a leading marine research organization working in The Bahamas for nearly 50 years, the Perry Institute for Marine Science believes that marine resource management and policy should be based on facts and evidence about the status of marine ecosystems and resources in addition to input from various stakeholders.So, what are the facts about sharks and turtles in The Bahamas and what information do policy makers need to know before making decisions regarding their management? In June 2018, a scientific paper published in the journal, Fisheries Management and Ecology, by Bahamian marine scientist Dr. Krista Sherman and colleagues, examined these very questions. Based on this review and other research studies, we briefly highlight below what we know and what we need to find out before making policy changes:

What is the status of shark populations?

- There are at least four species of sharks found in The Bahamas that are either considered endangered or critically endangered and several others are considered vulnerable to extinction with their populations declining (https://www.iucnredlist.org).

- Shark related tourism in The Bahamas is estimated to bring in $113.8 million, roughly 1/3 of the value of dive tourism nationally.

- While shark fishing was banned in The Bahamas in 2011, an earlier ban on longlining established to protect Bahamian fishermen in 1993 essentially ended the commercial shark fishery in The Bahamas by 1999.

- Studies of shark populations from 1979-2013 show a 22% decrease in tiger sharks while oceanic white tips and other species are highly migratory and leave The Bahamas.

- Shark populations are characterized by slow growth due to the fact that they are late maturing animals that produce only a few pups a year, so significant recovery of populations to historic levels is likely to take at least a decade if not more. For example, Feldheim and colleagues working in Bimini found sharks born in Bimini in 1993-1997 returned there to give birth 14-17 years later.

What about assertions of increased shark attacks?

- Over the past decade, shark attacks in The Bahamas have averaged one per year, with only two total fatalities (https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/trends/location/world/).

- For shark attacks that were classified as unprovoked (i.e., not involving spear fishing or other activities that attract sharks) (https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/maps/world-interactive/), the number of shark attacks from 2011-2020 since the shark ban has been in place was lower than from 2001-2010 or from 1991-2000.

Available evidence suggests that shark populations in The Bahamas are still likely to be low – likely remaining well below levels from 30 years ago, although an updated assessment of populations is needed.

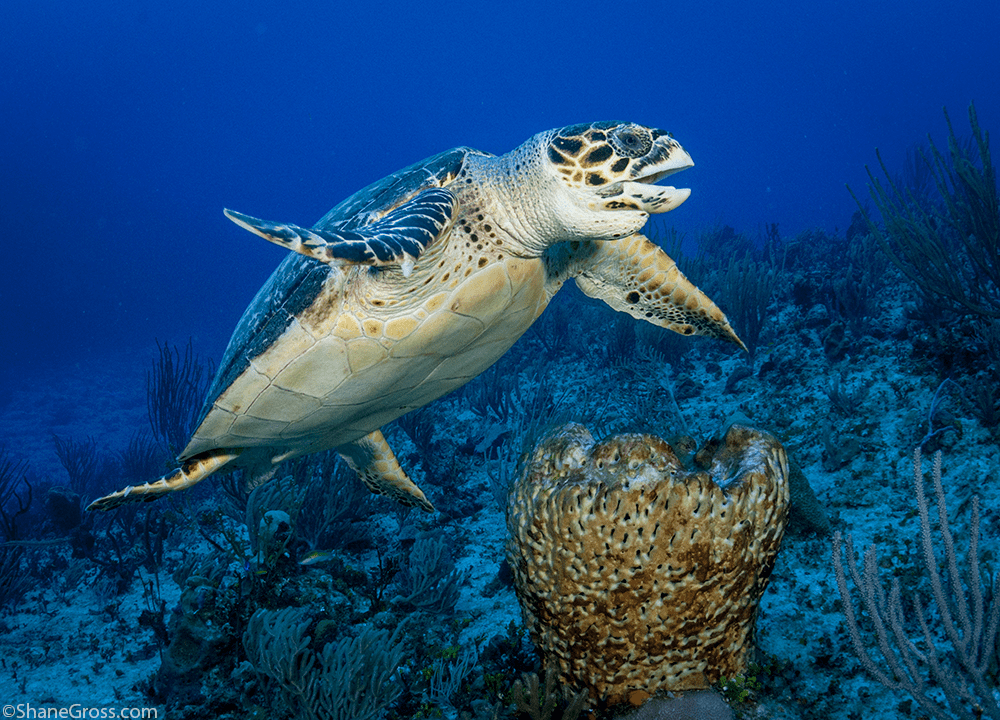

What about the status of sea turtle populations?

- As of 2017, of the four sea turtle species found in The Bahamas, one is considered endangered, one critically endangered and the rest vulnerable with populations globally in decline (https://www.iucnredlist.org).

- Despite the ban on turtle fishing in The Bahamas, turtle populations are still reduced due to pollution, diseases, and harvest as they migrate to other countries where they are not effectively protected.

- Like sharks and other vulnerable marine species, sea turtles are late maturing and have relatively low reproductive and juvenile survival rates, leading to slow population growth, making species recovery within a 10-year period unlikely.

- Other than humans, sharks – particularly tiger sharks – are some of the greatest predators of sea turtles, so if shark populations were to increase, we could expect to see a decrease in sea turtle populations.

What about the impact of sea turtles on fishery resources?

- While juvenile green turtles can eat lobster and juvenile conch, only loggerhead turtles eat conch and lobster and a wide range of prey throughout their life. Larger green turtles are vegetarians.

- Other species found in The Bahamas, like leatherbacks, eat jellyfish and hawksbills eat only certain species of sponges on reefs (not commercially harvested sponges).

So, what does all of this mean? While there may be some indications of increased populations for some species, data are limited and do not support widescale recovery of shark and sea turtle populations. Further, there are few studies examining the impact of turtle populations on conch and lobster populations, but based on the limited number of species that eat conch, the effect of sea turtles on conch populations is likely to be relatively low compared to fishing and other factors.As an island nation, the economy, ecology, and culture of The Bahamas is intricately linked to the health of its marine resources. From the coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves that are the foundation of the nearshore marine environment, to grazing species like parrotfish and green sea turtles, to key predators like Nassau grouper and sharks, the delicate balance of marine ecosystems is necessary for both a healthy environment and economy. People are an important part of this balance and we must also account for both the short and long-term well-being of communities that depend on these resources. We trust that the government will take scientific evidence into consideration when making decisions and will invest in the future of its marine resources by supporting critical research to evaluate management actions.

Download the full statement here:

https://www.dropbox.com/home/PIMS%20files?preview=PIMS+Statement+-+6+Nov+2020+Good.pdf

Photos on this page provided by Shane Gross.

The Bahamas Just Opened a Coral Gene Bank—Here’s Why It Matters

The nation’s first coral gene bank will preserve, propagate and replant coral to reverse devastation from rising ocean temperatures and a rapidly spreading disease Video courtesy of Atlantis Paradise Island.

This Is What Conservation Leadership Looks Like

From Interns to Leaders: How PIMS is Powering the Next Generation of Ocean Advocates Taylor photographs coral microfragments in the ocean nursery, helping monitor their fusion into healthy, resilient colonies

When Ocean Forests Turn Toxic

New study in Science connects chemical “turf wars” in Maine’s kelp forests to the struggles of Caribbean coral reefs — and points to what we can do next Lead author,

Who’s Really in Charge? Unpacking the Power Struggles Behind Madagascar’s Marine Protected Areas

Researchers head out to monitor Marine Protected Area boundaries—where science meets the sea, and local stewardship takes the lead. The Illusion of Protection From dazzling coral reefs to centuries-old traditions,

PIMS and Volunteers Step Up as Legal Battle Leaves Barge Grinding Reef in Fowl Cays National Park

Worn out but undefeated, the cleanup crew rallies around their paddleboard “workbench” in front of the stranded tug and barge—a snapshot of community grit after hours of underwater heavy‑lifting. Photo

Thriving Fish Spawning Aggregation Inspires Hope for the Future

Nassau grouper FSA in Ragged Island during January 2025. | © André Musgrove Fish Spawning Aggregations & Nassau Grouper Imagine witnessing thousands of fish gathering in a synchronized spectacle, moving